A Dutch design firm has proposed building floating annexes to the world’s major cities that would absorb growing urban populations and produce food and energy from the land-based cities’ waste.

They estimate that by moving just 13% of the world’s urban population onto these floating developments the impending global scarcity of arable land caused by population growth and environmental degradation can be averted.

This “Blue Revolution”, envisaged by the young Delft-based firm, DeltaSync, would lead to a balance between humanity’s needs and the limits of the planet.

Reviewing the relevant literature, the DeltaSync researchers* projected that by 2050 humanity would need lots more land to support life: 13 million sq km in the best-case scenario and 36 million sq km in the worst case. (It’s a big area in either case: China is 9.6 million sq km.)

With the world’s population of 7.2 billion today reaching 9.6 billion by 2050, according to the United Nations, the researchers say there will be growing pressure on the finite resources we need, such as fossil fuels, fresh water, phosphates and arable soil, not to mention space for living.

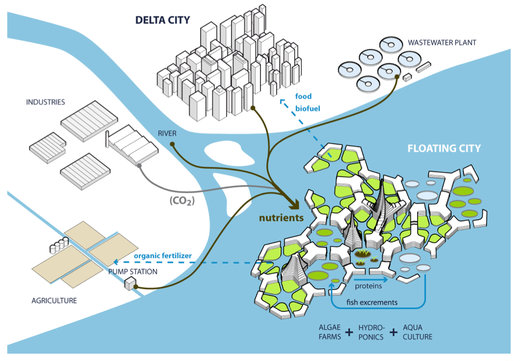

Floating cities attached to existing coastal cities would ease that pressure not only by giving people somewhere to live but, more importantly, by acting as massive farms for algae, which can produce biofuels, food and livestock feed – all while eating the carbon dioxide and polluting inorganic nutrients cities produce.

As an energy source, algae turn carbon into high density natural oils while at the same time extracting inorganic nutrients from the water. According to the literature, potential yields of microalgae are estimated to be five to 60 times higher than yields of oilseed crops, while algae consumes 150 to 300 times less water.

Algae also contain protein and carbohydrates, and can be used as food for humans, and as feed for fish and some livestock. The researchers discovered that chicken feed can be up to 10% algae. For pigs that goes up to 35%. Cows and other ruminants can’t, however, digest algae carbohydrates.

DeltaSync sees a powerful symbiosis between the land city and its offshore annex: in goes the waste, pollutants and carbon dioxide (captured from smokestacks) and out comes food and biofuels, which otherwise would require arable land to grow.

Part of the beauty of the vision is that algae food and biofuel production on water is far more efficient than on land – 10 or more times more efficient per surface area unit, they say.

As for how the floating cities would work structurally, DeltaSync is already fairly advanced in its thinking.

Formed after a group of civil engineering and architecture students from Delft University of Technology won a competition sponsored by Royal Haskoning with their design for a floating city on a lake near Amsterdam in 2006, DeltaSync now specialises in floating city concepts.

In goes the waste, pollutants and carbon dioxide, out comes food and biofuels (DeltaSync)

Since then they’ve been commissioned to produce a study of how floating cities might work on the high seas for the California-based Seasteading Institute. That study, released in December, proposed clusters of floating concrete caissons, with a 50m x 50m platform as the basic physical unit of the “seastead”.

Meanwhile, DeltaSync believes that 44% of the world food demand can be met by these floating algae farms using the waste nutrients and carbon dioxide currently produced by cities.

The sea area required would be a drop in the ocean: the firm says the Blue Revolution would need a total floating area of just 585,000 sq km – around the size of Madagascar.

In the optimal ratio, DeltaSync says, 13% of the urban population would live in the floating cities.

With Rotterdam University of Applied Science and the BlueRevolution Foundation, DeltaSync is researching further the potential of floating developments for particular cities around the world.

DeltaSync says it is now working on the first phase by mapping the nutrient cycles of three promising cities to see how exactly nutrients can be used to produce food and biomass.

* The researchers were B. Roeffen, B. Dal Bo Zanon, and K.M. Czapiewska of DeltaSync and R.E. de Graaf of Rotterdam University. See their paper here