How the Islamic Republic is set to become the land bridge that connects the continents.

Following the deal struck between negotiators on 14 July this year over gearing Iran’s nuclear development toward exclusively peaceful purposes, it is widely expected that sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council will be lifted sometime in January.

Once this happens, Iran will be free to start doing business with the many national delegations that have been arriving in Tehran over the past six months for sales presentations, and it will be able to pay with the million extra barrels of oil a day it will have to sell on world markets.

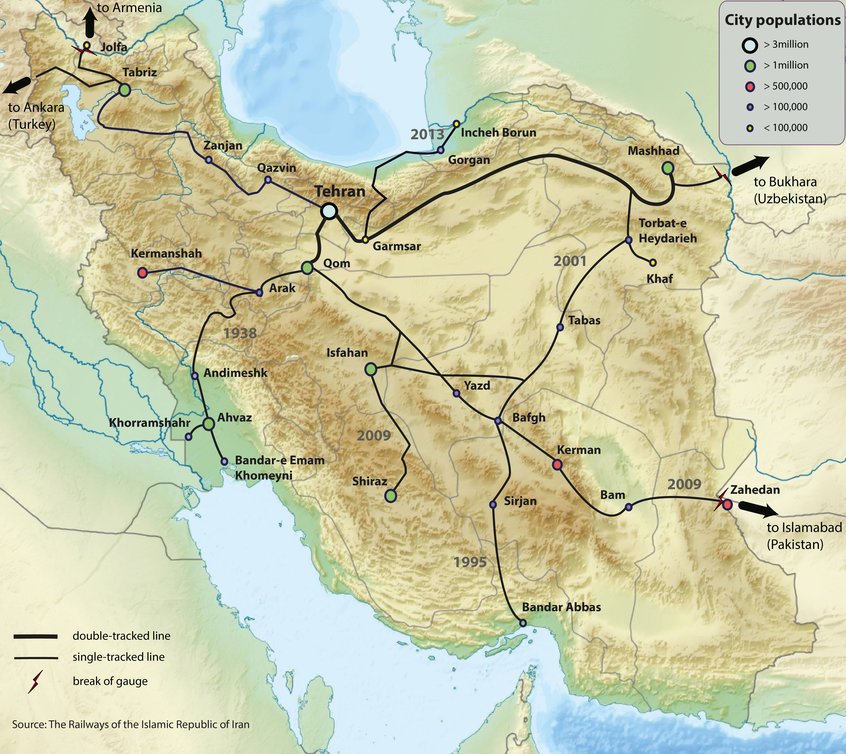

A high priority for Iran is the creation of a genuinely national rail network. At present Iran has just less than 13,000km of track. This is 4,500km fewer than in the UK, a country with about the same number of people living on a patch of Earth seven times smaller.

Iran’s major cities are separated by hostile deserts and high mountains. Long-distance travel by road is exhausting and dangerous (there are seven times more road deaths in Iran than in the UK) and although air transport is expanding rapidly, it cannot rely solely on planes to meet domestic demand for intercity freight and passenger travel.

Iran’s rail network: the lines in service now (RAI/GCR)

What service there is is poor. The system consists of largely unelectrified, single-track lines centred on Tehran that miss out large cities such as Hamedan (population: 500,000), and require slow, circuitous journeys to travel between neighbouring cities such as Shiraz and Bandar Khomeyni. This means that only about 11% of the people who travel in Iran do so by train.

The government’s plans

The government is planning a major expansion. The director of the Republic of Iran Railways (RAI), Mohsen Poursaeed-Aqaei, said in October that his agency had identified $25bn worth of rail projects, plus “incentive packages” to attract domestic and foreign investment.

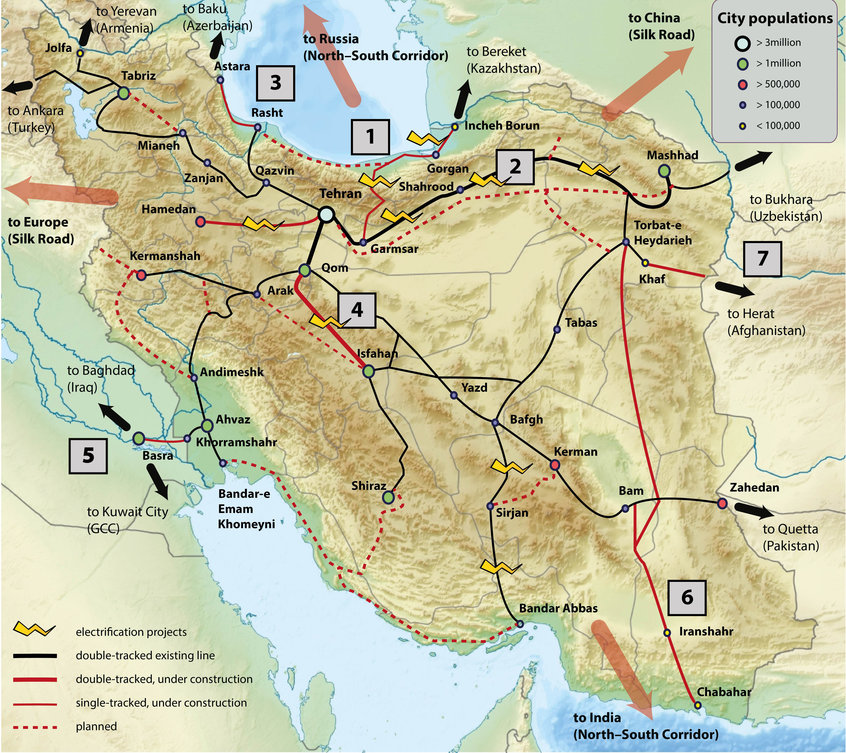

By 2025, existing lines will be electrified and double-tracked and about 12,000km of new lines will be built, nearly doubling the size of the network.

Some groundwork has already been done. Twenty years ago the sparsely-populated south-east of the country had scarcely any rail lines. But Iran needed to move containers north from its Gulf ports, and so it completed the link between Bandar Abbas and Bafgh in 1995.

With that link, and the 2009 connection between Isfahan (population 1.7 million) and Shiraz (population 1.5 million), the country achieved the skeleton of a national service. The drive now is to put some flesh on the bones.

Continental crossroads

As well as getting its own people and goods moving, Iran is eager to come into its own as a great hinge between Europe, Asia and Africa. Making Iran a giant crossroads are two grand trade routes envisaged between the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic oceans. One is the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and the other is China to Europe Silk Road.

The idea behind the INSTC is that containerised goods will travel from the Port of Mumbai to Iran’s Gulf coast – bypassing Pakistan – from where they will be able to reach Moscow and Europe in half the time taken by the Suez Canal.

As well as saving time, the route has been estimated to save $2,500 for every 15 tonnes of cargo.

Iran, Russia and India signed a convention initiating the INSTC way back in 2000, but Iran’s pariah status has prevented progress. Indian exporters are very keen, which is why one leading Indian newspaper greeted the 14 July deal with jubilation.

The other axis of the crossroads is China’s Silk Road, arguably the infrastructure project with the highest priority of all in Beijing.

A high-speed standard gauge line running through central Asia would slice through a knot of broad gauge lines in the states of the former Soviet Union, and speed up the flow of goods to Europe, compared to sailing round the long way.

So, the stakes riding on the Iran’s rail schemes are high, both for the Iranian economy and for the whole of Asia as it reconfigures itself for the 21st century. Here are seven of the most significant schemes that are underway now, or that will shortly go ahead.

Iran’s future network: The seven new lines planned and under construction (RAI/GCR)

1. Tehran to Central Asia

An early win in Iran’s rail revolution will be the boosting of the historic line from Tehran north-east to Turkmenistan, facilitating the flow of goods, particularly grain and oil, between the former Soviet Central Asian Republics bordering the Caspian Sea (Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan) and the Persian Gulf. Russia is a key player in this upgrade.

On 23 November, RAI and Russia Railways subsidiary RZD signed an agreement worth $1.3bn to electrify the 495km section of rail between Garmsar, on Tehran’s outskirts, and the village of Incheh Borun on the country’s north-eastern border with Turkmenistan.

The old line is actually part of Iran’s first great national railway, the Trans-Iranian, built between 1927 and 1938, but it needs modernising.

The 36-month contract will involve building power stations and overhead lines, 32 new train stations and widening 95 tunnels to accommodate the stouter rolling stock used on the Soviet system.

The RAI’s Poursaeed-Aqaei said the aim was to increase the capacity of the line to 8 million tonnes of goods a year.

The project will be financed by the Russian government out of a $5bn export credit line. Iran insisted that all electric locomotives for the deal had to be made in Iran, allowing Iran’s manufacturers to absorb new skills and technology.

An interesting side effect is that it will turn the sleepy village of Incheh Burun (population 1,764; reached by railroad in 2013) into a key node in a major Eurasian arterial route.

Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev expects the new line to boost rail traffic between Iran, Turkmenistan and his country from 3 million tonnes a year to 20 million tonnes by 2020, The Railway Gazette reports.

Kazakhstan’s rail links with China would make this route one of several strands in China’s “Silk Road high-speed railway” – standard-gauge links between China, central Asia, Iran and Europe.

2. All the way to China

While Russian money is paying for a modern high-speed Turkmenistan link, the Chinese are about to begin electrifying the line that runs roughly parallel to it: the 1,000km double-tracked route between Tehran and the shrine city of Mashhad.

In June, Iranian and Chinese officials finalised an agreement to electrify this line, with 85% of the $2.1bn cost to be financed through Chinese loans.

Completion of this work is expected to take 42 months, followed by a five-year maintenance period. It will be carried out by Iranian infrastructure engineer Mapna Group and China’s CMC and SU Power.

When this line is fully modernised, 70 Chinese locomotives will zoom along it at 250km/h. Together with improved track and signals, this is expected to cut the journey between Tehran and Mashhad from about 12 hours to six, and increase freight capacity to 10 million tonnes a year.

Along with the Incheh Borun route, this will be another strand of China’s Silk Road. The proposal was put forward by He Huawu, the chief engineer of the China Railway Corporation.

His route runs from Urumqi in western China, through Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, hitting Ashgabat in Turkmenistan before crossing south into Iran and down to Mashhad.

From there it would join Iran’s east-west network leading to Turkey and eastern Europe.

Huawu said container trains and passenger trains could run on the same route. The only difference would be speed. A passenger train could run at 250-300 km/h, whereas a container train could run at 120 km/h.

3. Iran to Moscow

Key to the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) is a railway running from Russia down through Azerbaijan, through Iran to the Persian Gulf, facilitating trade between Russia’s populous east and India and southeast Asia via the Indian Ocean.

The new link is required because the old Soviet railway passed from Azerbaijan and Armenia, and those two countries are engaged in one of the region’s frozen conflicts: the line has been closed for more than 20 years.

In May this year, the rail heads of Iran, Russia and Azerbaijan agreed that Russia would build the rail line from Rasht on Iran’s Caspian coast, to Astara in Azerbaijan.

According to reports in the Russian press, the decision was taken out of “exasperation” with Iran for failing to build the 170km line in 2013. RAI did build the 200km Qazvin-Rasht section, but then ran out of funds, so it said.

The Rasht route will branch off Iran’s main northwest line at Qazvin, pass across the mountains to the Caspian coast to Astara, thereby re-connecting western Europe to Southeast Asia for the benefit of India, Russia and the other signatories to the INSTC. The plan is to open it next year, after which Astara will be turned into a special economic zone.

What is not so clear is the future of Iran’s proposed $3.2bn link with Armenia. This is a high priority for Armenia, of course, but not, it seems, for Russia. Vladimir Yakunin, the chief executive of Russian Railways, said in June 2015 that the project would not be “like opening a window to nowhere, to the wall of a neighboring building”.

Armenian officials had hoped that Russian investment would be forthcoming, but following Yakunin’s remarks Armenia is also in talks with China over funding.

4. The high-speed showpiece

The link between the Tehran, Qom and Isfahan is going to be the showpiece of the entire network: a modern double-tracked line running at 400km/h – the only genuinely high-speed project presently under way.

Work on the $2.7bn scheme began in February 2015, undertaken by the China Railway Engineering Corporation and Iran’s Khatam Al Anbia Construction. Completion is scheduled for 2019.

A considerable part of the work will involve building or rebuilding stations, and some of this has been won by Arep, the multidisciplinary design arm of French state-owned rail operator SNCF.

It will rebuild stations in Tehran and Qom as modern multi-modal transport hubs, and do the same for Mashhad on the north-eastern line.

Etienne Tricaud, the head of Arep’s board of directors, said in July: “Tehran railway station is 80 years old now, and it is not compatible with present-day needs. We have to present a comprehensive plan for 170 ha of land at this station so that high-speed inner-city and suburban trains, as well as electric and metro trains, can transport passengers in the city centre.”

Iran’s Bank of Industry and Mine will provide $1.8bn of the finance for the work, underwritten by the China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation.

Meanwhile, reports in the Iranian press in May 2015 that a British private company had agreed to build a railway from Isfahan to meet the Qom-Kermanshah line at Arak have died away.

According to Mohammad Ebrahim Rezaei, who represented the central city of Khomein at the Iranian parliament, the Iranian Ministry of Road and Urban Development had already given the go-ahead to the mystery investor, and it was to have been the privately built railway in Iranian history. Â

5. Basra, at last

In June 2015, Iran began laying the first ever track between Khorramshahr and Basra in Iraq, thereby creating an eventual junction between the Silk Road and the regional rail system being built by the Gulf Co-operation Council countries. It will require a 12km length of track on the Iranian side of the border, a 700m-long bridge over the Arvand River and a 32km stretch on the Iraq side.

According to Iranian officials, the integration of the railways will take place in the next 20 months. Currently, as many as 20,000 Iranians use the Shalamcheh border crossing daily to travel to Iraq, a figure that rises to 50,000 during Shia religious anniversaries, when Iranian Shia travel to Karbala, Najaf and Baghdad.

Abbas Akhoundi, Iran’s Minister of Roads and Urban Development, commented: “With the operation of this railway line, we hope transportation will improve for the travellers. It will also connect us to the eastern Mediterranean nations and lead to a transformational change in the transit of goods and passengers.”

6. The Eastern Corridor

Chabahar is the Iran’s southernmost city, and also its best access to the Indian ocean. It is also at one end of what former president Mahmud Ahmadinejad called “Iran’s Eastern Corridor” connecting Chabahar to central Asia, the Caspian and the Caucasus.

In much the same way as Russia felt compelled to hurry Iran along at Rasht, India is taking a hand in the expansion of the Chabahar port and is also lending finance and advice to the construction of the railway. The aim is to sidestep Pakistan and compete with the new Chinese-built port a few miles along the coast at Gwadar in Pakistan.Â

It has been calculated that freight moving by rail from Chabahar or Bandar Abbas takes 30 days to travel by rail to Bandar Anzali on the Caspian Sea, move by ship to the Kazakh rail system and reach St Petersburg, compared with 45-60 days on the Suez route.

Tehran has suggested that the Indians lend a hand with the 500km stretch between Chabahar and the line between Ban and Zahedan, which is located by the borders of Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

This would tie Chabahar in with the main Iranian rail system and give Indian exporters access to the distant markets beyond Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan.

Negotiations over the terms of this deal have been bumpy, according to reports in the Indian press, with Delhi concerned that if it were to take an equity state in the link, a future Iranian government may expropriate it. The Iranians have responded with soothing words.

7. The $3 trillion prize

The possibility of building a railway to Herat in western Afghanistan has been proposed and abandoned at regular intervals for the past hundred years or so, mostly by officials of the British and Russian empires.

The Iranian plan now is to build a branch to Herat from the line being built between Chabahar and Torbat-e Heydarieh. The work for this scheme is under way, and the line now stands about halfway to the border.

Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai, the president of Afghanistan, has reportedly expressed his support for a plan to continue the line on the Afghan side of the border, and the local officials have lobbied in favour of it.

Iran is reportedly willing to pay for the link to Herat, and has begun planning for an extension to Mazar-i-Sharif in the north of the country, which is the only substantial city with a rail service (it goes north to Uzbekhistan).

The possibility of a railway in Afghanistan – which is on the direct route between Iran and China – would be an essential step to the economic recovery of the country, if only to enable a start to be made on mining the country’s vast mineral wealth.

A line to Herat would enable the exploitation of Hajigak region, which contains Asia’s largest deposit of iron ore – one estimate puts its value at $3 trillion – and access to it is an acknowledged motive for India’s willingness to finance the Chabahar railway.

Given the prizes on offer, it is not surprising that Iran and India are pressing ahead with the line, however the difficulties of operating in Afghanistan in its present state of disorder are obvious: it has been called the ‘world’s most dangerous railroad‘.

Conclusion

If sanctions against Iran are dropped next year, the country will be hard pressed to cope with the consequences of its success.

The expectation among those countries and construction companies looking to do business with Tehran is that there will be a long infrastructure and construction boom that will address equally urgent needs to expand its downstream oil and gas industries, tackle the serious housing shortage, modernise the health and education systems and expand its power system sufficiently to cope with the inevitable increases in demand. Â

Just as important as these priorities is the expansion and modernisation of the rail system, not least because of the amount of investment that it will attract from neighbouring states who also have something to gain from a first-class system: from being the regional pariah, Iran has been transformed into the country that none of the others in the wider region can do without.

Top photograph: Passengers on board the Yazd to Tehran service. Only 11% of journeys are presently made by train in Iran (Franco Pecchio/Wikimedia Commons)

Comments

Comments are closed.

In June I took an overnight train from Yazd to Tehran. Comfortable, but not exactly quick. Most local people prefer bus travel as it’s quicker, more frequent and cheaper.