The US state of California has suffered three years of below-average precipitation, and is now running out of water.Â

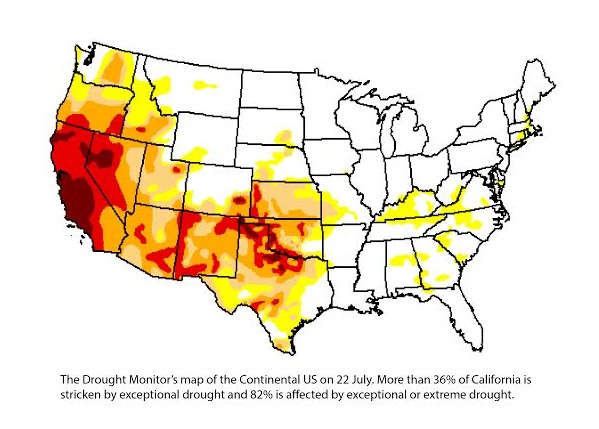

In February, the federal government’s Drought Monitor agency decided that 9% of the state was undergoing an "exceptional drought", the first time in the 15-year history of the organisation that any part of California had reached that status.

Five months later, that designation applied to 36% of the state, with another 44% subject to the lesser category of "extreme" drought. Jerry Brown, the governor of California, has asked every Californian to cut their water use by 20%.

This would be a serious enough situation in any inhabited region, but California is extraordinarily vulnerable to water stress. It has 80,500 farms and ranches that grow $45bn worth of produce, including half of the US’s fruit and vegetables. This agricultural activity generates another $100bn in the wider economy.Â

Despite this fertility, much of the state is, in its natural form, a semi-desert, and depends on irrigation to sustain production. Now water allocation to farmland has been cut by 50%, the maximum extent allowable by law, and the US Department of Agriculture has warned that this could have "large and lasting effects on fruit, vegetable, dairy, and egg prices".

Farmers in the Central Valley, which is at the heart of the agriculture industry, paid $140 for an acre-foot (that is, 1.2 million litres) of water last year; now they pay $1,100.

The cause of the dry weather is an area of high pressure in the Pacific, which meteorologists have named the "ridiculously resilient ridge". This may disappear tomorrow, of course, but some climate scientists take an apocalyptic view of long-term changes in the Golden State’s climate.Â

Andrew Freedman, the managing editor of advocacy group Climate Central, has pointed out that tree-ring data show that the three-year dry period is among the 10 worst droughts to hit California in the past 500 years, and is part of a broader western American drought that has lasted for roughly 13 years.

California produces more than half of America’s fruit, but the cost of water for irrigation has risen tenfold–

This, he says, raises the spectre of a "megadrought" that will fundamentally change the natural environment – and that’s the one the built environment has to deal with it.Â

Water we make ourselves

In the midst of this anxiety about the future of western America’s water resources, there is a growing interest in the construction of desalination plants as a kind of capital-intensive, brute force solution to the problem.Â

Altogether, 15 desalination plants are being proposed for the coastline between Los Angeles and San Francisco. Whether these schemes go ahead or not will depend to a great extent on what happens at the plant that has reached site, at the coastal town of Carlsbad near the Mexican border.Â

This scheme gives an indication of what will be involved if the state as a whole decides to go down this route.

"Everybody is watching Carlsbad to see what’s going to happen," according to Peter MacLaggan, the vice president of Poseidon Resources, the Boston firm that is going to run it.

The first lesson from Carlsbad is that it takes a long, long time to build a desalination plant. Poseidon reckons it has spent 12 years planning it, and six years taking it through the permitting and licensing procedures of all relevant regulators, from the California Coastal Commission and the State Lands Commission to the Regional Water Quality Control Board.Â

Altogether, more than a dozen local, state and federal bodies have a say in whether a desalination plant goes ahead. The most important of these is probably the water purchase agreement that enables a developer to raise project finance.

It also takes a long time to build, although in this case the construction and the regulatory approval process ran side by side. Work on the Carlsbad site began in November 2009, and the plant is not expected to be operational until 2016.

Costs are both large and unpredictable. When work began, the cost of the scheme was put at $300m. The present estimate for the out-turn cost is $1bn. Partly as a result of this, the price of desalinated water is high: San Diego County has agreed to pay $2,000 per acre-foot, which is about double the going rate, even in an extreme drought.

That means that the authority will pay more than $3bn over 30 years for less than 7% of the county’s water requirements.Â

Alongside negotiations with public agencies, a scheme of this kind has to deal with legal challenges from private groups, which are usually directed at the agencies that grant licences and permits rather than the project’s backers.

Carlsbad faced more than a dozen legal battles, for example those launched by the Surfrider Foundation, the Coastkeeper NGO and the Planning & Conservation League.Â

These groups attacked the Californian Land Commission’s approval of the scheme, based partly on its cost. Marco Gonzalez, the attorney for Surfriders, commented that Carlsbad was "going to be the pig that will try for years to find the right shade of lipstick. This project will show that the water is just too expensive".

As well as producing colourful soundbites, these battles can last a couple of years or so, and can involve extremely involved and detailed arguments. All of this adds to the burden of risk that the project’s managers and funders have to shoulder.Â

Finally, even a scheme the size of this one – the largest in the Western hemisphere – will ameliorate rather than solve San Diego County’s water shortage.

Carlsbad is designed to produce 50 million gallons of water a day, which is enough to meet the needs of 300,000 people – which, as mentioned above, is 7% of the requirements of the county. Poseidon has reached the "late planning" stage with another scheme at Huntington Beach in the southern suburbs of Los Angeles.

This will be another 50 million gallon facility located by the AES Huntington Beach Power Station, and is scheduled to be operational by 2018. It will need to build many more of them if desalination is to contribute a significant percentage of the region’s water needs.Â

‘Fresh squeezed water’

The debate over the move to mass desalination as a mainstay of the state’s water needs is controversial in the scientific community.Â

There is an ecological debate over the damage caused to local marine life, both from being sucked into the plant’s intake and from the concentrated brine that is pumped back into the sea.Â

There is also a debate about the energy required to power the plant. Those who advocate desalination point out that modern osmosis systems are more energy efficient than the older evaporate-and-condense models, which require operators to keep enormous kettles constantly boiling.Â

The modern plants work by forcing seawater through membranes that filter out its impurities. It is possible that improvements in technology will reduce the cost of desalination.

The science of membranes is still developing – only last week a big news story broke in that corner of the research community about an MIT study that found that forward osmosis was less efficient than reverse osmosis.

However, environmental groups are taking the line that desalination should be pursued only as a last resort.

As the Natural Resources Defence Council wrote in a recent blog, the state’s first line of defence should be "conservation, stormwater capture through the use of green infrastructure, water-use efficiency, and wastewater recycling". And as, so far, the state has not banned the watering of lawns with hosepipes, there may be some steps still to take to cut per capita water use.

For example, it was reported on Saturday that southern California has responded to the governor’s call for a 20% voluntary reduction in water used by raising its consumption 8%…