A review of the tall buildings that were completed in 2014 reveals the increasing popularity of the 200m-plus project – and China’s extraordinary domination of it.Â

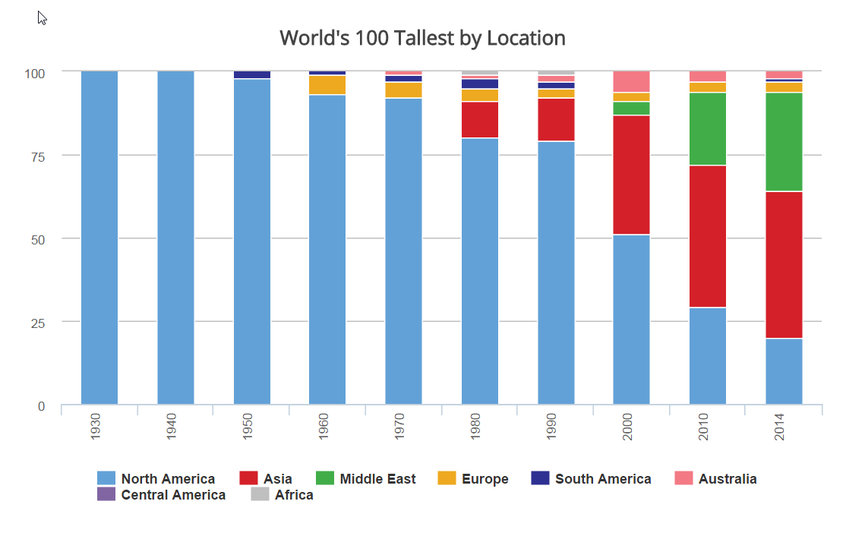

For the seventh year in a row it built more of them than anybody else, and last year it was responsible for almost twice as many as everybody else put together.

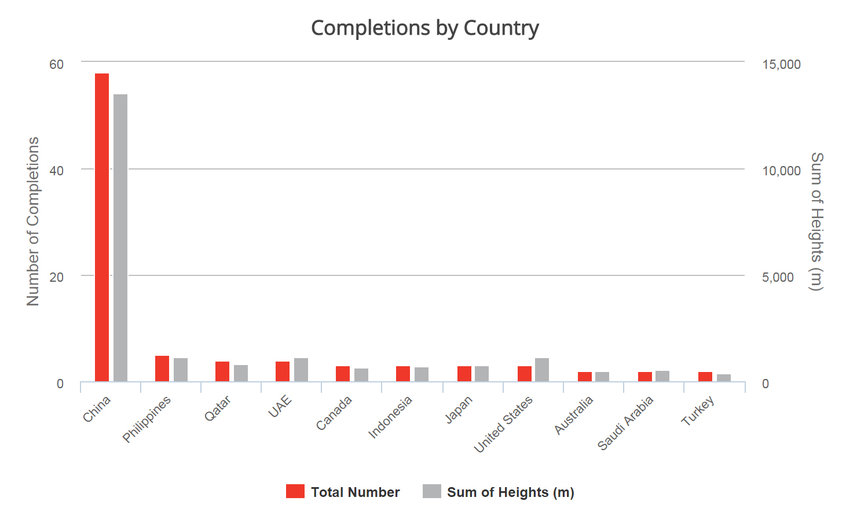

Tall buildings completed in 2014 by country

The information is contained in the annual review of the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, a research organisation based at the Illinois Institute of Technology, which maintains a database on tall (200m-plus) and supertall (300m-plus) buildings around the world.Â

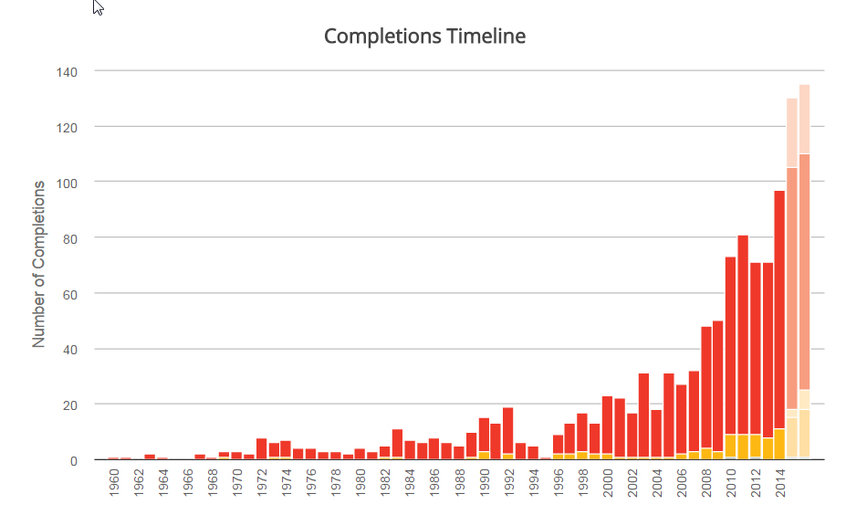

This year’s round-up reveals that 97 were completed, more than in any other year. Of these, 76% are in Asia, and 60% are in China.

One city, Tianjin, is this year’s tall building capital of the world, with 6% of the global total. It completed just short of 1.25km of towers, just a few metres ahead of Wuxi, a rapidly growing metropolis located 50km west of Shanghai at the mouth of the Yangtze.Â

The figure is an eloquent testimony of the rising economic power of China and the other countries of the Pacific Rim.

The rise of Asia as a tall building market

The city that came third in terms of length was New York, which produced three tall buildings, including the tallest of the year, the 541m One World Trade Centre, which is presently number three in the world rankings. The other two project were the 298m, 4 World Trade Centre and One57, a 306m residential tower.

The database charts an interesting change in the way these buildings are getting built, as well.Â

More than half are built using composite materials, which in tall buildings usually means a mix of concrete and steel, as steel is strong in terms of tension whereas concrete is resistant to compression. The number of concrete-only buildings has declined dramatically, from 61% of buildings in 2013 to 38% in 2014.

This year, the number of completions is set to increase again, although the balance may tilt a little. Of the top 20, only half will be located in China; three will be in the United Arab Emirates, three will be in Moscow and two will be in Riyadh.Â

The tallest will be the 632m-high, 128-storey Shanghai Tower, which has already topped out. This will be the tallest building in China until 2016, when it will be overtopped by the 660m-high Ping An Finance Centre, presently on site in the neighbouring city of Suzhou. This in turn will be beaten in 2020 by the 729m-high mixed-use Suzhou Zhongan Centre.

How the market has grown

In terms of world rankings, the 1km-high Kingdom Tower in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, is on course to take that prize from Dubai’s 828m-high Burj Khalifa in 2018.Â

The Burj looks likely to retain its title until then, as nothing higher is being seriously proposed. One notable absentee from this list is Sky City in Changsha, a 836m skyscraper project that was to have been built in an impressive 90 days, but which seems to have been quietly abandoned.

In terms of what the institute calls "visionary" schemes – that is, ones located in the extensive grey area between a funded building project and an architect’s doodle – the largest is the 4km-high X-Seed 4000 project in Tokyo, which has the distinction of being the tallest building ever to be fully designed.Â

This concept, which somewhat resembles Mount Fuji, was produced by the Taisei Corporation, and whatever its practical chances of ever being built might be, it does explore the particular engineering challenges faced by an inhabited structure that high.Â

For example, conventional lifts, even the modern versions that travel at 18m per second, would be replaced by maglev versions, and inhabitants would have to deal with different weather conditions and pressure variations along its length.Â

Photograph: Tianjin’s skyline, featuring Skidmore, Owings & Merril’s CTF Finance Centre (Source: SOM)